In the bustling activities room of the BakerRipley Kashmere Senior Center in northeast Houston, local seniors gathered to chat and share stories of survival. Many have endured the Gulf Coast’s worst storms, bringing floods, fierce winds, and prolonged power outages.

Seventy-three-year-old Emily Barriere, wearing a blue baseball cap, recounted her experiences. “I’ve been through maybe five hurricanes,” she said, recalling the devastation. “I lost everything.”

Barriere has lived in a nearby senior apartment complex since Hurricane Harvey flooded her home in 2017. Most recently, she faced the wrath of Hurricane Beryl. The storm brought back familiar fears, but the wind sounded different this time. “Like a whistle,” she recalled.

When Beryl hit, the power went out. Barriere grabbed a radio, her phone, and a lamp, praying for the best. “I just started praying. I said, ‘Lord, just don’t let it do us too bad.'”

Like Barriere, 2.3 million electric customers across the Houston area were left without power. As the oppressive July heat set in, those days without electricity were unbearable. “It wasn’t nice. But what could I do but try to bear it?” she said. “And let me tell you, it’s not the kind of heat we were brought up in. This is a different kind of heat now.”

Barriere saw ambulances arrive for neighbors who were on oxygen or couldn’t handle the rising temperatures. Despite the vulnerability of many elderly residents, Barriere’s senior complex didn’t have a generator. “I don’t understand it. This is a senior place for people who have paid their dues. That generator stuff, it’s ridiculous.”

For some, the outages stretched over a week. Harris County recorded 20 deaths linked to Hurricane Beryl, seven of which were due to heat exposure during the power outages. All victims were 50 years or older, according to the Harris County Institute of Forensic Sciences.

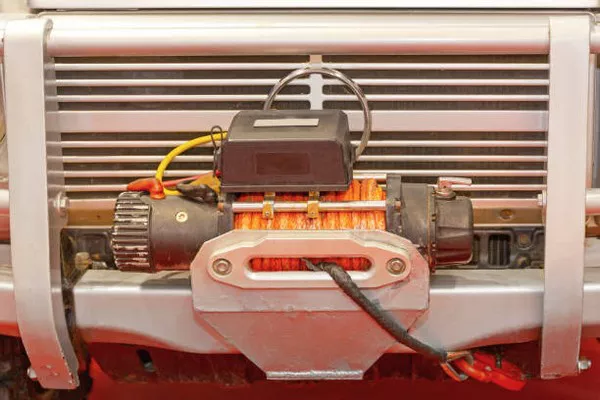

With the growing frequency of power outages, demand for generators has surged, particularly among older populations. Aaron Jagdfeld, CEO of Generac Power Systems, noted a sharp increase in demand following Texas’s February 2021 freeze. “Every time there’s another outage, people get closer to saying, ‘That’s it. I’m ready to spend money to solve this problem,’” he said.

In-home consultations for Generac’s standby generators in Texas were five times higher in July when Beryl struck compared to the previous six months. Houston residents, in particular, are reaching this tipping point faster than anywhere else in the country, Jagdfeld said.

However, the high cost of generators remains a barrier. While Generac’s customers typically own homes valued at around $450,000, most low- and moderate-income people can’t afford such a large investment. “The majority don’t have the money to go out and buy a generator,” said Margo Weisz, executive director of the Texas Energy Poverty Research Institute.

Additionally, Beryl sparked a rush on generators, leaving many, particularly the elderly, unable to find or transport one. For those living in apartments, like many seniors and low-income individuals, there are also restrictions on generator use.

Nonprofits have tried to step in, providing limited support. After Beryl, organizations like Woori Juntos, a Houston nonprofit, delivered ice and supplies to seniors without power. Executive Director Hyunja Norman described the heartbreaking scene of an elderly man fanning his ill wife, who was later hospitalized. Her group managed to secure a small generator to power a fan and air conditioner in a common area, offering some relief.

For seniors, Norman emphasized, backup power is a necessity. “We are pushing for generators in all senior housing,” she said. “They need to have a generator.”

Elaine Morales-Díaz, policy director at disaster-relief nonprofit Connective, echoed that sentiment. “Generators are a lifesaving tool in our disaster-preparedness toolkit,” she said, urging for wider access until the grid becomes more resilient.

“How can we increase access to them until we are able to build a more resilient infrastructure and system for our community?” Morales-Díaz asked. “It’s a matter of life and death.”